Think lying on an operating table is the most dangerous part of surgery? It’s actually what you don’t feel or see—tiny blood clots forming quietly while you’re out cold—that can flip a patient’s fate from routine to risky. Surgeons and anesthesiologists fight an invisible battle every day. Why the urgency? About 900,000 cases of venous thromboembolism (VTE)—aka blood clots—hit people in the U.S. each year, and more than half are hospital-related, with surgical patients topping the risk list. Scary, right? But with sharp protocols, most are stopped dead in their tracks before they do harm.

Why Surgery Trips the Clot Alarm

Let’s face it—surgery sets off everything the body does to stop bleeding. But sometimes, the very system that saves us turns into a ticking time bomb. When surgeons cut through tissues, your body’s clotting army jets into action, and immobility (thanks, anesthesia) gives clots extra time to form. This is why anesthesiologists’ routines go far beyond monitoring your breathing—they make crucial calls on how to keep blood flowing smoothly while you’re knocked out. Certain surgeries, like orthopedic or cancer operations, are worse offenders, raising risk up to 50-fold compared to non-hospitalized folks.

Age plays a role—after age 60, risk climbs steadily. Obesity, smoking, birth control, hormone therapy, history of cancer, and even family genes help stack the deck. And the kicker? Immobilization during long surgeries lets blood pool in the legs, the perfect storm for clots called deep vein thrombosis (DVT), which sometimes travel to the lungs (pulmonary embolism, or PE) and can kill within hours. As explained in this resource on anesthesia and blood clots, immobility and altered circulation during surgery both play big roles.

Mechanical Methods: Not Just Wrapping the Legs

Mechanical prevention strategies aren’t as simple as strapping compression boots on every patient. Think of it as a toolkit with several options, each targeting the main reason clots form—stagnant blood in the veins. Sequential compression devices (SCDs) are the all-stars: they rhythmically squeeze the legs, mimicking walking and squeezing blood back to the heart. Not only are new devices quieter and more comfortable, but some units actually tell staff if they’re used correctly, cutting down on “human error.”

Graduated compression stockings look like regular knee-high socks but apply firm, gentle pressure that tapers toward the thigh, helping to keep blood from pooling. Anesthesiologists also roll patients and reposition them when possible during extra-long operations—anything to keep circulation on the move. Early ambulation is huge; the sooner a person’s up and walking, the less likely blood will sit still. Even for patients who can’t walk right away, simple leg exercises (like ankle pumps) get blood moving. Here’s a quick-reference table of mechanical methods and key usage details.

| Device/Method | How It Works | When Used |

|---|---|---|

| Sequential Compression Devices (SCDs) | Inflates/squeezes legs rhythmically | Most surgical and immobile patients |

| Graduated Compression Stockings | Applies graded pressure to legs | Moderate-risk or ambulatory patients |

| Early Ambulation | Gets patient walking ASAP | Post-op, when condition allows |

| Simple Leg Exercise | Ankle pumps/flexion during surgery or recovery | Patients unable to get up right away |

Some patients can’t use compression (think: open wounds or severe artery problems). In those cases, mechanical prevention takes a backseat, and the focus shifts to the next chapter—pharmacologic strategies.

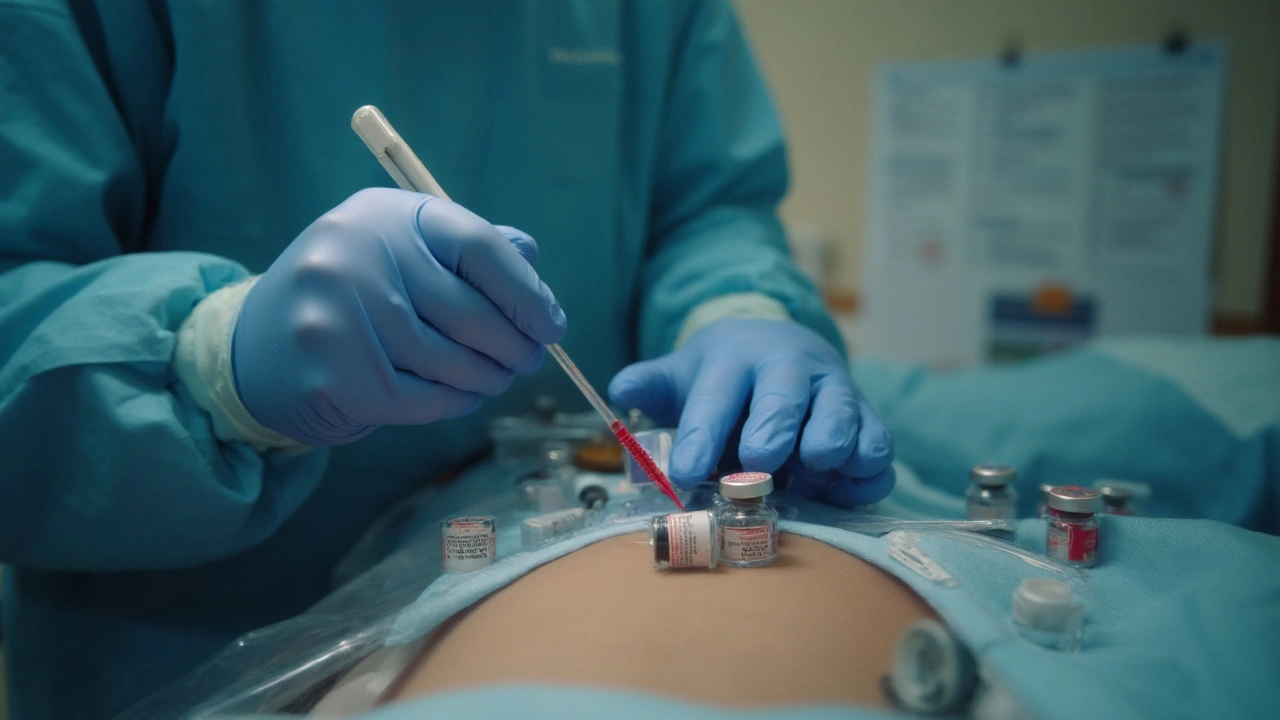

Pharmacologic Approaches: Meds That Thin, But Don’t Spill

Mechanical options cover the basics, but for higher-risk cases, medications that slow or “thin” the blood are essential. There’s an art to picking the right drug, dose, and timing. Too little, and the clotting risk rages on. Too much, and bleeding might become a new emergency. Heparin (both unfractionated and low-molecular-weight), fondaparinux, and direct oral anticoagulants are the drugs turning the tides.

Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is now the gold standard for many surgeries. It’s a tiny syringe once or twice a day, reducing DVT and PE rates by up to 70% in hip and knee replacements. For lower-risk cases or where bleeding is a big fear, tiny doses or shorter courses are used. There’s no “one size fits all”—factors like kidney function, weight, age, and bleeding risk get debated every time.

Here’s another thing: sometimes, both mechanical and pharmacological approaches are combined, especially for orthopedic or trauma surgeries. That double-team approach can drive risk to near zero. Meds usually start hours after the surgeon checks for bleeding but always sooner rather than later. And, yes, there are even oral meds used for clot prevention in select patients, opening up easier therapy for some who need a simpler routine post-op.

| Medication | Dosing | Common Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) | Once/twice daily injection | Hip/knee replacement, trauma surgery |

| Unfractionated heparin | Subcutaneous/intravenous, multiple times daily | High bleeding risk, renal impairment |

| Fondaparinux | Daily injection | Some orthopedic/cancer surgeries |

| Direct oral anticoagulants | Pill once/twice daily | Selected cases, ease for outpatients |

One practical tip: patients often worry about “blood thinners” and bruising or bleeding. Clear communication before and after surgery about risks, the signs to look for, and when to call in can make all the difference in catching issues early.

The Human Factor: Routines, Checklists, and Automation

Protocols only protect patients if the team uses them right. Hospitals have moved way beyond “doctor’s orders on a clipboard.” Now, most ORs rely on detailed checklists and bundle approaches: nobody starts or finishes surgery without confirming clot prevention, swapping stories, and double-checking the right devices and doses. Some larger centers use digital reminders, and many electronic health records won’t let teams move forward until they confirm mechanical or medication-based prevention is in place.

Real-life complications almost always follow protocol gaps—either a missed med dose, forgetting to restart SCDs after patient repositioning, or lack of patient movement. Studies show structured, repeated team huddles catch problems before they start. And when something does slip, the team reviews how and why, then updates processes for everyone. Automating SCDs to alert staff when not worn or out of sync is a surprisingly low-cost fix that can cut complications up to 30%.

Education starts before surgery, too. Nurses and anesthesiologists talk patients and families through what to expect from prevention routines, why the noisy leg boots matter, and why walking as soon as possible is not just a “nice to have”—it’s essential for survival. When everyone plays their part, things work. It’s a team sport, every time.

Real-World Cases: Lessons from the Frontlines

Let’s put this into context with some patient stories. Take Max, a 48-year-old set for his first knee replacement. He’s told he’ll wear SCDs before, during, and after surgery and get a daily LMWH shot for two weeks. They explain bruising is normal, but if the pain, swelling, or redness shoots up his leg, he’s got to call ASAP. Max walks out of the hospital on day three, never has a clot, and gets back on the golf course a month later.

Then there’s Linda, 62, with breast cancer surgery and a high BMI. Her chart flags high clot risk. The anesthesiologist debates with the surgeon about starting blood thinners, since the surgery is long, and cancer adds extra clot risk. They settle on LMWH, compression boots, and aggressive physical therapy, which gets her moving a day after surgery. Linda does great and never needs a blood transfusion.

On the flip side, an overlooked dose or unapproved “compression break” has landed patients back in the ER with DVTs post-discharge. Hospitals analyze these as “never events”—the sort no one wants to repeat. The takeaway? Prevention needs to be continuous, not just something stamped on the chart during the procedure.

The stats drive the point home. In high-risk orthopedic surgeries, combining mechanical and medication approaches drops clot rates from 15% to under 2%. And in trauma care, aggressive prevention slashes risk even further. When protocols get briefed to every staff member and patients are in the loop, blood clots lose their edge—one small victory at a time.

Comments (21)