The FDA Orange Book is the official government list that tells you which generic drugs are approved and can be safely swapped for brand-name drugs. It’s not just a directory-it’s the rulebook pharmacies, doctors, and insurers use every day to decide what gets filled at the counter. If you’ve ever picked up a generic pill and wondered if it’s really the same as the brand, the Orange Book is why you can trust that it is.

What the FDA Orange Book Actually Is

The full name is Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations. That’s a mouthful, but it breaks down simply: it’s a list of drugs the FDA has approved as safe and effective, along with notes on whether generics can replace them. The book started in 1980, but its modern form comes from the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act. That law was designed to speed up generic drug approvals without letting big pharma lock up the market with endless patents. Today, the Orange Book is digital, updated every month, and contains over 16,000 approved drug products. Roughly 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics-and the Orange Book is the reason that number is so high. Without it, pharmacists wouldn’t know which generics are interchangeable, and insurance companies wouldn’t know which ones to cover.How Generic Drugs Get Listed

Generic drugs don’t go through the same long, expensive testing as brand-name drugs. Instead, they use a faster path called the Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA. To get approved, a generic maker must prove their drug is bioequivalent to the original. That means it delivers the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate. The original drug used for comparison is called the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). The FDA picks this based on which version was first approved and has the most complete data. When you search the Orange Book, you’ll see the RLD marked with a “Yes” in the RLD column. All the generics that match it will say “No.” For example, if you look up Lipitor (atorvastatin), you’ll see Pfizer’s version as the RLD. Then you’ll see dozens of generic versions listed below it-all with the same active ingredient, same strength, same way of taking it (tablet, oral), and all rated as therapeutically equivalent.Therapeutic Equivalence Codes (TE Codes)

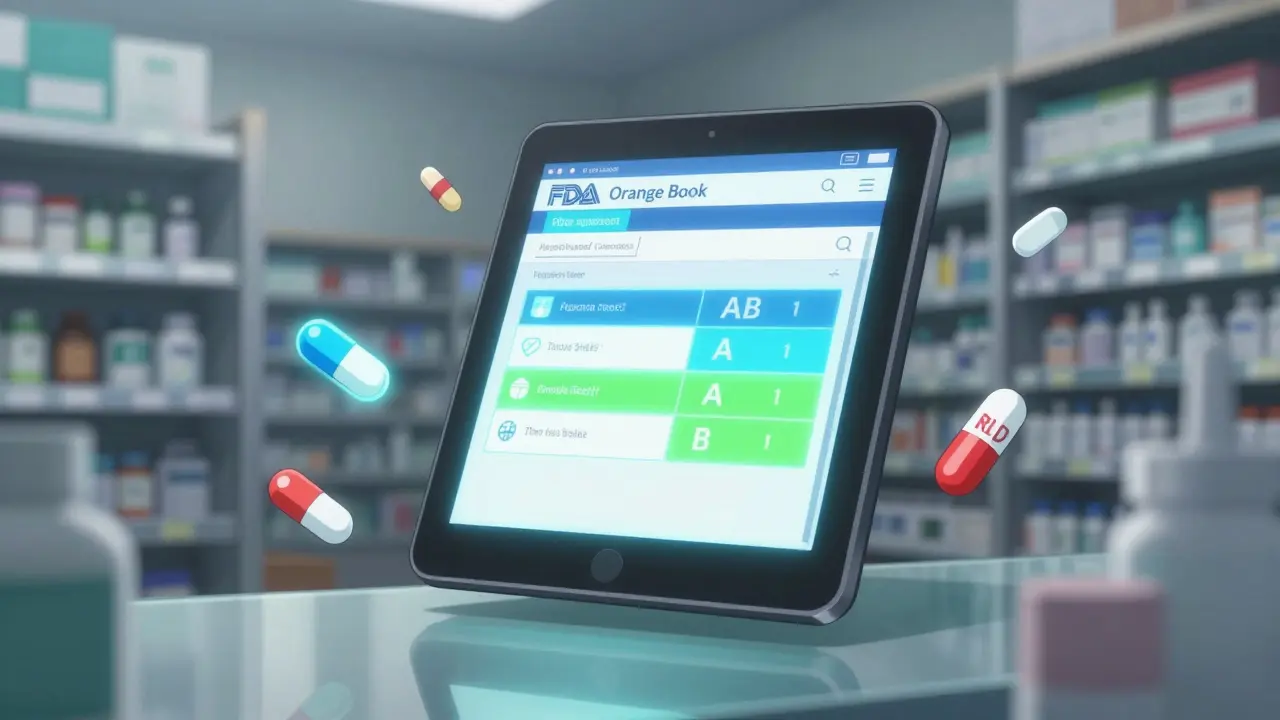

Here’s where things get practical. Every drug in the Orange Book gets a TE code. These two-letter codes tell you if a generic is interchangeable with the brand. The most important ones are:- A = Therapeutically equivalent. This generic can be substituted without any concern.

- B = Not equivalent. These are either not proven to work the same way, or there’s a known issue (like different absorption rates).

- BN = Single-source brand. No generics are approved yet.

- AB = Bioequivalent and meets all standards. This is the gold standard for substitution.

Authorized Generics: The Hidden Option

There’s another kind of generic you won’t find in the Orange Book: the authorized generic. These are the exact same drug as the brand, made by the same company, just sold without the brand name. For example, the maker of Nexium might sell a generic version of esomeprazole under its own name, but without the purple capsule and fancy packaging. Authorized generics are listed under the original New Drug Application (NDA), not the ANDA. So while they’re in the FDA’s database, they don’t show up in the Orange Book’s generic section. The FDA keeps a separate list of these, updated quarterly. They’re often cheaper than the brand but cost the same as regular generics. Some pharmacies even stock them because they’re identical to the brand-no risk of differences in fillers or coatings.Patents and Exclusivity: The Hidden Barriers

The Orange Book doesn’t just list drugs-it lists patents. When a brand-name company files its drug for approval, it must tell the FDA about every patent it holds that covers the drug’s ingredients, formula, or how it’s used. These get published in the Orange Book. Why does this matter? Because generic companies can’t launch until those patents expire-or unless they challenge them in court. If a generic maker files an ANDA and says a patent is invalid or won’t be infringed, the brand company can sue. That triggers a 30-month legal hold, delaying the generic’s release. In 2022, there were over 14,000 patents listed in the Orange Book-up from 8,000 in 2005. Critics say this is “patent evergreening,” where companies file new patents on minor changes just to block generics. The FDA says it’s trying to stop this, especially with new rules in 2023 that require clearer patent descriptions.How to Use the Orange Book

The Electronic Orange Book is free and easy to use. Go to the FDA’s website and pick your search method:- Search by active ingredient (like “metformin”)

- Search by brand name (like “Glucophage”)

- Search by manufacturer or application number

What’s Not in the Orange Book

Not everything gets listed. Over-the-counter (OTC) drugs aren’t evaluated for therapeutic equivalence. Why? Because they’re not prescribed, and their safety profiles are well-established. You won’t find allergy meds, pain relievers, or antacids in the main equivalence tables. Also, drugs that are discontinued-no longer made or sold-appear in a separate section. They’re listed with no RLD or TE code, just as a historical record. And if a generic has only a “tentative” approval, it won’t show up in the Orange Book yet. That means the FDA is still reviewing something-maybe a manufacturing issue or a patent dispute. You’ll find those on Drugs@FDA, but not in the Orange Book.Real-World Problems and Fixes

Even with all this data, things get messy. Pharmacists report confusion with combination drugs-like inhalers with three active ingredients. The TE code might say “AB,” but in practice, switching brands can cause breathing issues because the delivery device isn’t identical. A 2023 survey found that 62% of pharmacists had at least one case where state substitution laws didn’t match the Orange Book’s rating. Some states allow substitutions only for “AB” drugs, others allow “A” too. The system works, but it’s not foolproof. To help, companies like DRX integrate Orange Book data into pharmacy software. But even then, 41% of users still need extra help interpreting the codes. That’s why training matters-pharmacy schools now spend 8-10 hours teaching students how to read the Orange Book properly.What’s Next for the Orange Book

The FDA is working on a “Digital Orange Book” by 2025. The goal? Real-time updates, better search tools, and clearer data structure. Right now, updates happen monthly, but new approvals can take weeks to appear. There’s also a new API that healthcare systems use to pull data directly into their software. Over 2 million searches happen every month. That’s how deeply embedded this system is in U.S. healthcare. The bottom line? The Orange Book isn’t just paperwork. It’s the engine behind generic drug competition. It saves patients billions each year. It keeps drug prices down. And it’s one of the most important, yet least talked about, tools in American medicine.Is the FDA Orange Book the same as the Purple Book?

No. The Orange Book lists small-molecule drugs-pills, injections, creams-that are chemically synthesized. The Purple Book lists biological drugs, like insulin, vaccines, and monoclonal antibodies. These are made from living cells, not chemicals, so they follow different rules. The Purple Book was created in 2009 for biosimilars, which are like generics for biologics.

Can I trust a generic drug if it has an ‘AB’ code?

Yes. An ‘AB’ code means the FDA has confirmed the generic is bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. It has the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration. It’s tested in people to make sure it works the same way. Millions of patients take AB-rated generics every day without issues.

Why does my pharmacy sometimes switch my generic even when I didn’t ask?

Most insurance plans require the cheapest equivalent drug. If your prescription doesn’t say “dispense as written,” the pharmacy can legally switch to any generic with the same TE code. If your brand has multiple AB-rated generics, the insurer will pick the lowest-cost one. You can always ask for the brand, but you’ll likely pay more out of pocket.

How long does it take for a new generic to appear in the Orange Book?

After the FDA approves a generic, it usually shows up in the Orange Book the next month. The approval letter is issued first, then the data is uploaded. If there’s a patent dispute or incomplete paperwork, it can be delayed. But under current FDA timelines, most generics are listed within 30-45 days of approval.

Do all generic drugs have to be listed in the Orange Book?

Yes-if they’re approved under an ANDA and are for prescription use. All approved generic drugs must be listed. But if a drug is discontinued, or if it’s an over-the-counter product, it won’t appear in the main therapeutic equivalence section. Authorized generics are listed under the brand’s NDA, not separately.

Comments (15)