CDI & Thyroid Disorder Symptom Checker

This tool helps identify potential overlapping symptoms of central cranial diabetes insipidus (CDI) and thyroid disorders. Please select the symptoms you've been experiencing:

Your symptom analysis will appear here. Select symptoms and click "Analyze Symptoms" to get insights.

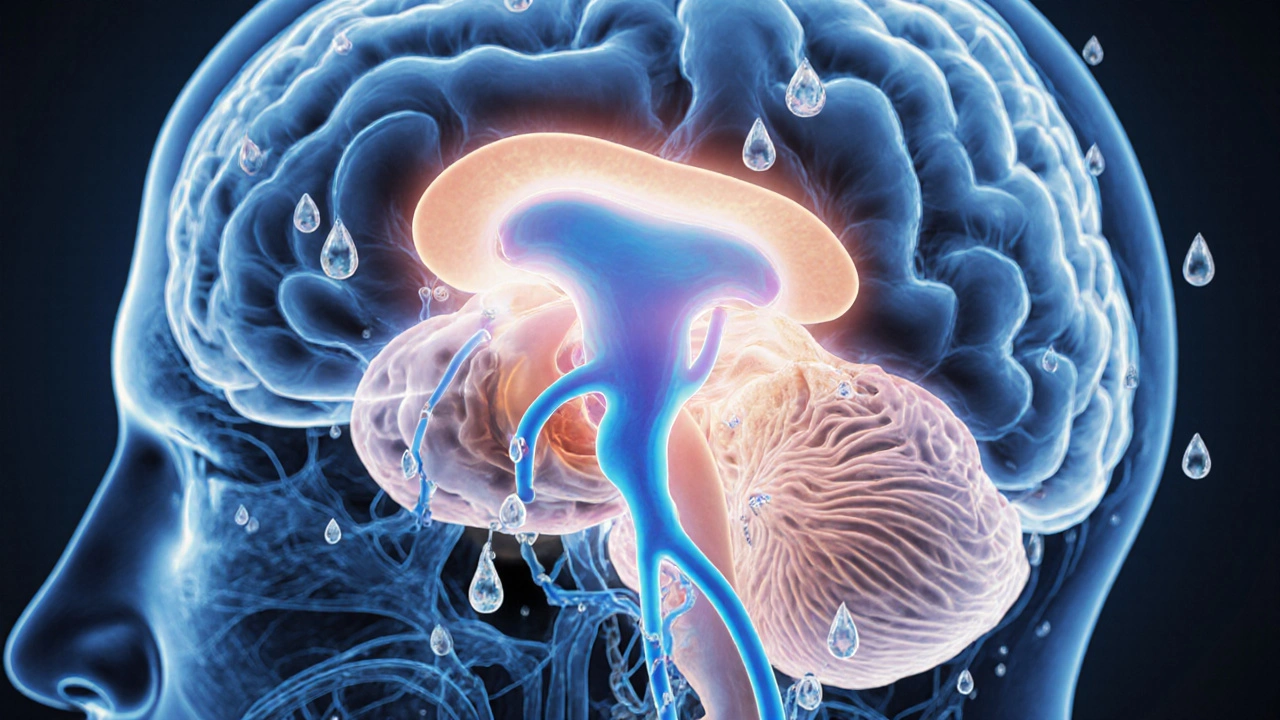

Ever wondered why a problem with water balance can show up alongside thyroid issues? The link isn’t a coincidence - both systems share the same master controller, the pituitary gland. Below you’ll learn what central cranial diabetes insipidus is, how it can intersect with thyroid disorders, and what steps doctors take to sort out the puzzle.

What is Central Cranial Diabetes Insipidus?

Central cranial diabetes insipidus is a rare disorder where the brain fails to produce enough antidiuretic hormone (ADH), also called vasopressin. The hormone normally tells the kidneys to re‑absorb water; without it, you pee large volumes of dilute urine and feel constantly thirsty.

Typical signs include:

- Excessive urination (polyuria) - often more than 3 liters a day

- Intense thirst (polydipsia) that doesn’t subside with normal fluid intake

- Dry skin and mucous membranes

Causes range from head trauma, tumors, infections, to autoimmune damage of the hypothalamic‑pituitary axis.

Brief Overview of Thyroid Disorders

Thyroid disorders cover any condition that alters the production of thyroid hormones (T3 and T4). The most common forms are hypothyroidism (under‑active thyroid) and hyperthyroidism (over‑active thyroid), often driven by autoimmune mechanisms.

Key players:

- Hashimoto's thyroiditis, an autoimmune attack that destroys thyroid cells, leading to hypothyroidism.

- Graves' disease, an antibody‑mediated stimulation that ramps up hormone production, causing hyperthyroidism.

Symptoms vary widely - weight gain, fatigue, cold intolerance for hypothyroidism; weight loss, heat intolerance, tremor for hyperthyroidism.

Why the Two Conditions Talk to Each Other

The pituitary gland sits at the crossroads of water balance and thyroid regulation. It releases ADH from the posterior lobe and thyroid‑stimulating hormone (TSH) from the anterior lobe. Damage to the hypothalamic‑pituitary region can therefore knock out both hormone pathways.

Autoimmune pan‑hypophysitis - inflammation that targets the entire pituitary - is a documented cause of simultaneous CDI and thyroid autoimmunity. In such cases, antibodies that attack thyroid tissue (anti‑TPO, anti‑TG) often coexist with antibodies that impair ADH secretion.

Another bridge is medication. Some drugs used for thyroid disease (e.g., high‑dose lithium) can suppress ADH release, while others for CDI (desmopressin) may affect thyroid hormone metabolism.

Clinical Clues That Both Systems Might Be Involved

Patients rarely present with textbook‑perfect symptoms. Here are red‑flag patterns that suggest a combined problem:

- Persistent polyuria despite proper desmopressin dosing - look for unexplained weight changes or heart‑rate spikes that hint at thyroid dysfunction.

- Thyroid labs (TSH, free T4) that swing erratically after starting ADH therapy - the stress of chronic dehydration can alter thyroid hormone conversion.

- Headache or visual field defects alongside water‑balance issues - a pituitary macroadenoma can compress both the posterior and anterior lobes.

Spotting these patterns early helps avoid misdiagnosis and unnecessary tests.

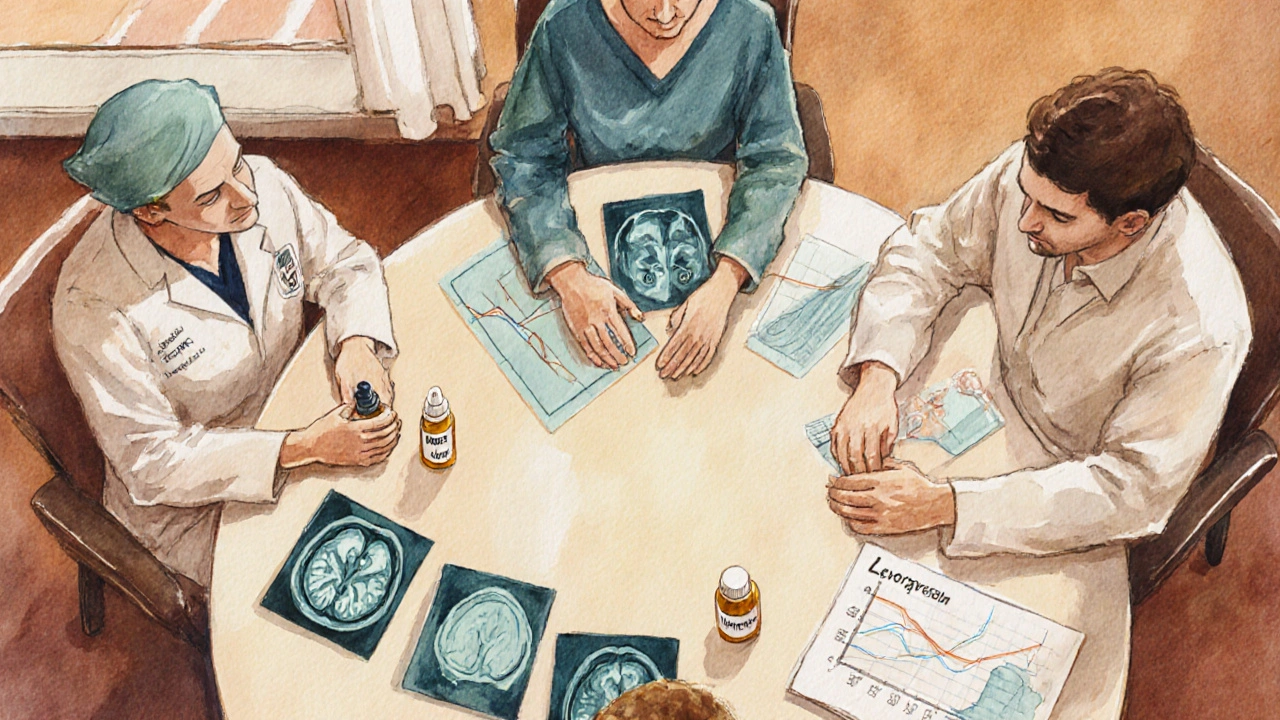

How Doctors Diagnose the Overlap

Step‑by‑step workup usually follows two parallel tracks: confirming CDI and evaluating thyroid function.

- Water‑deprivation test: Patients are monitored without fluids while urine output and osmolality are measured. A failure to concentrate urine points to CDI.

- Desmopressin challenge: After the water‑deprivation phase, synthetic ADH (desmopressin) is given. A sharp rise in urine osmolality confirms a central (pituitary) cause.

- Pituitary MRI: High‑resolution imaging detects lesions, inflammation, or stalk thickening. Contrast‑enhanced scans can highlight autoimmune hypophysitis.

- Thyroid panel: TSH, free T4, and thyroid antibodies (anti‑TPO, anti‑TG, TSI) establish whether hypo‑ or hyper‑thyroidism is present.

- Additional labs: Serum sodium, plasma osmolality, and cortisol are checked because ADH loss can disturb electrolytes and stress the adrenal axis.

Putting the results together lets clinicians map out which part of the pituitary is affected and whether an autoimmune process is at play.

Treatment Strategies When Both Are Present

Management is a balancing act - replace what’s missing while keeping the other system stable.

- Desmopressin (DDAVP) remains the cornerstone for CDI. Dosing is individualized; oral tablets, nasal spray, or melt‑away formulations are options.

- Thyroid hormone replacement for hypothyroidism - usually levothyroxine titrated to keep TSH in the mid‑normal range. Over‑replacement can worsen fluid loss.

- Antithyroid drugs (methimazole, propylthiouracil) for hyperthyroidism - monitor for side‑effects like agranulocytosis, which can compound infection risk in pituitary inflammation.

- Immunosuppression if autoimmune hypophysitis is confirmed - high‑dose corticosteroids can shrink inflammation, sometimes restoring endogenous ADH and TSH production.

- Monitoring - regular urine volume logs, serum sodium checks, and thyroid labs every 3‑6 months help catch drift early.

Patients often need a multidisciplinary team: endocrinology, neurology, and sometimes neurosurgery if a tumor is involved.

Quick Checklist for Patients and Clinicians

| Step | What to Do | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Record daily urine volume and fluid intake. | Detect patterns that may signal inadequate ADH or thyroid‑related diuresis. |

| 2 | Order water‑deprivation and desmopressin challenge. | Confirm central vs. nephrogenic cause. |

| 3 | Get pituitary MRI with contrast. | Identify lesions or inflammation that affect both lobes. |

| 4 | Run a full thyroid panel plus antibodies. | Pinpoint hypo‑ or hyper‑thyroidism and autoimmune status. |

| 5 | Start desmopressin; adjust dose based on urine osmolality. | Restore water balance without over‑hydration. |

| 6 | Begin thyroid therapy (levothyroxine or antithyroid drugs) as indicated. | Normalize metabolism and reduce systemic stress. |

| 7 | Schedule follow‑up labs every 3 months. | Catch dose drift before complications arise. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can hypothyroidism cause diabetes insipidus?

Hypothyroidism itself doesn’t directly suppress ADH, but severe hypothyroidism can lead to dehydration that mimics polyuria. True central diabetes insipidus usually stems from pituitary damage, which can coexist with autoimmune thyroid disease.

Is the water‑deprivation test safe for someone with thyroid problems?

When performed under close supervision, the test is safe. Clinicians monitor heart rate, blood pressure, and temperature because hyperthyroid patients may have an exaggerated response to fluid loss.

Will desmopressin affect my thyroid medication?

Desmopressin acts on the kidneys and doesn’t interfere with thyroid hormone metabolism. However, keeping fluid balance stable helps maintain consistent absorption of oral levothyroxine.

Can steroids cure both conditions?

High‑dose steroids may shrink autoimmune inflammation of the pituitary, potentially restoring ADH and TSH secretion. They do not treat primary thyroid gland damage, so hormone replacement is still needed.

What signs suggest I need an MRI?

New headaches, visual field loss, sudden worsening of polyuria, or abnormal pituitary hormone panels all warrant imaging to rule out a tumor or hypophysitis.

Comments (19)