Imagine trying to hear your partner speak in a quiet room, but their voice sounds muffled-like they’re talking through a pillow. Then you realize it’s not them. It’s you. That’s how many people with otosclerosis describe their first real clue something’s wrong. This isn’t just normal aging or earwax. It’s abnormal bone growing where it shouldn’t, locking up the tiny stirrup bone in your middle ear and slowly stealing your ability to hear low tones. And it’s more common than you think.

What Exactly Is Otosclerosis?

Otosclerosis is a condition where bone in the middle ear starts growing abnormally, especially around the stapes-the smallest bone in your body, shaped like a stirrup and only about 3.2mm long. Normally, this bone vibrates freely when sound hits your eardrum, passing those vibrations into the inner ear. But in otosclerosis, new bone forms around the stapes, fusing it to the oval window-the opening to the inner ear. It’s like rust seizing a hinge. The bone doesn’t just grow; it hardens into a rigid mass that can’t move. Sound can’t get through.

This isn’t cancer. It’s not an infection. It’s a slow, silent remodeling of bone tissue. Histology shows it starts as soft, spongy bone rich in blood vessels, which then turns dense and immobile. The result? Conductive hearing loss-meaning sound can’t travel efficiently from the outer ear to the inner ear. Your ears still work. Your brain still works. But the middle ear’s mechanical link is broken.

Who Gets Otosclerosis and Why?

You’re most likely to develop otosclerosis if you’re a woman between 30 and 50. About 70% of cases occur in women, and it often gets worse during pregnancy, suggesting hormones play a role. Genetics matter too. If a parent or sibling has it, your risk jumps significantly. Studies have found at least 15 genetic links, with the RELN gene on chromosome 7 being the strongest predictor.

Ethnicity also plays a part. People of European descent have the highest rates-up to 0.4% of the population. In contrast, rates are lower in Asian and African populations. In the UK, about 1 in 200 people have it, making it one of the top causes of hearing loss in adults under 50. It rarely causes total deafness, but left untreated, hearing can drop by 15-20 dB over five years. That’s the difference between hearing a normal conversation and needing someone to shout.

How Do You Know You Have It?

The classic sign is trouble hearing low-pitched sounds. You might not notice it at first. But then you realize:

- You can’t hear whispers unless the person is right next to you.

- People say you’re mumbling-even when you’re not.

- You turn up the TV, but still miss parts of the dialogue.

- You hear ringing in your ears (tinnitus), especially when it’s quiet.

Unlike age-related hearing loss (presbycusis), which hits high frequencies first, otosclerosis hits the low end-around 500 Hz. Unlike Meniere’s disease, you won’t get sudden dizzy spells or fluctuating hearing. The loss is steady, gradual, and usually worse in one ear at first.

Audiometry confirms it. A hearing test will show an air-bone gap of 20-40 dB-meaning sound travels poorly through the air to your inner ear, but bone conduction (vibrating the skull) works fine. That’s the fingerprint of conductive hearing loss. Speech tests usually show good word recognition, which helps rule out inner ear damage… at least early on.

When Otosclerosis Spreads to the Inner Ear

In 10-15% of cases, the abnormal bone growth doesn’t stop at the stapes. It creeps into the cochlea-the snail-shaped part of the inner ear that turns vibrations into nerve signals. When that happens, you get sensorineural hearing loss too. This is harder to treat. It’s not just a mechanical problem anymore; the hair cells in your cochlea are damaged.

This mixed hearing loss progresses slower-about 0.5-1.0 dB per year-but it’s permanent. Once the inner ear is involved, surgery won’t fix it. That’s why early diagnosis matters. The sooner you catch it, the better your chances of keeping your hearing intact.

What’s the Best Way to Treat It?

You have two main options: hearing aids or surgery.

Hearing aids are the first step for many. They amplify sound, compensating for the blocked transmission. About 65% of people start here. They work well, especially for mild to moderate loss. But they don’t stop the disease. The bone keeps growing. And if you develop inner ear damage later, hearing aids become less effective.

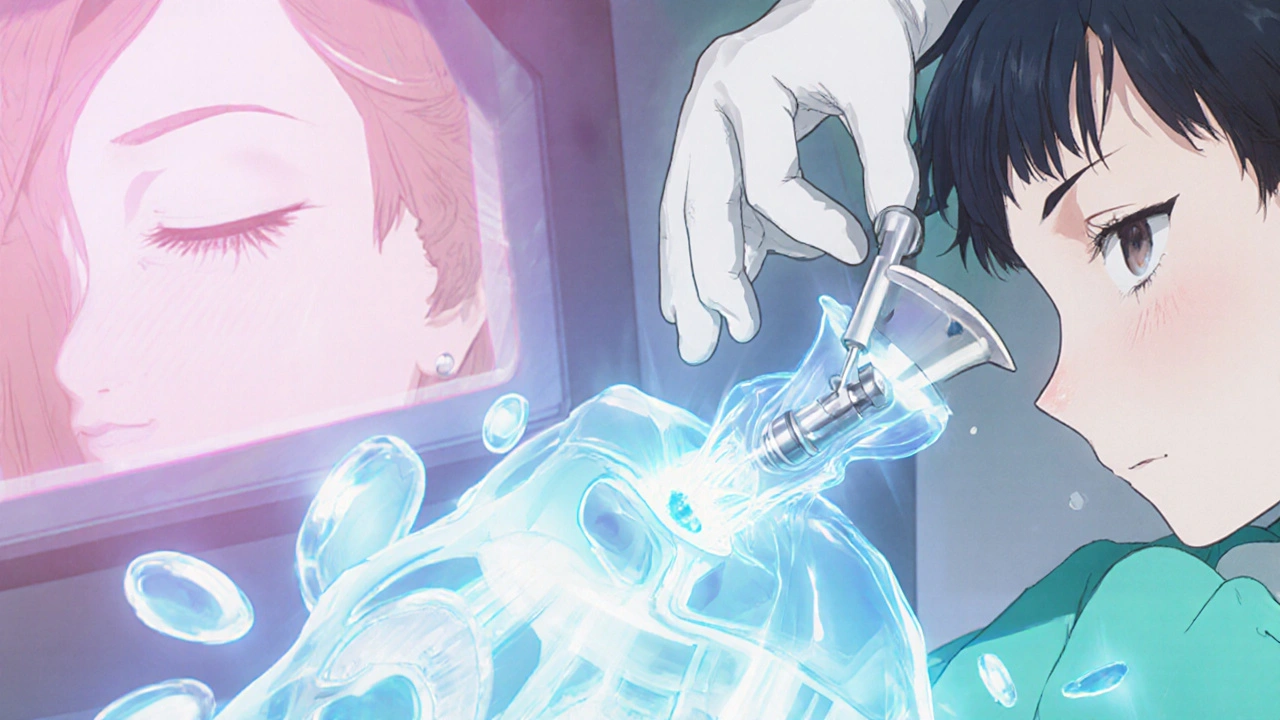

Surgery-specifically stapedotomy-is the gold standard. Instead of removing the whole stapes, the surgeon makes a tiny hole in the footplate and inserts a prosthetic piston, usually made of titanium or platinum. This piston connects the incus (another middle ear bone) to the inner ear, bypassing the fused bone. The procedure takes about an hour, is done under local or general anesthesia, and most people go home the same day.

Success rates are high. Around 90-95% of patients regain functional hearing-meaning they can hear normal conversation without amplification. The new FDA-approved StapesSound™ prosthesis, with its titanium-nitride coating, reduces scarring and has a 94% success rate at 12 months. That’s better than older models.

But it’s not risk-free. In about 1% of cases, patients suffer sudden, permanent sensorineural hearing loss. Tinnitus can worsen. Dizziness is common for a few days. These risks are rare, but they must be discussed before surgery. And if you’ve had a failed surgery before, revision success drops to 75%.

What About Medications?

There’s no cure, but there’s hope for slowing it down. Sodium fluoride, a mineral used in dental care, has shown promise in clinical trials. A 2024 study found it reduced hearing deterioration by 37% over two years compared to placebo. It’s not approved everywhere, but some UK and US clinics prescribe it off-label for patients who aren’t ready for surgery or have early-stage disease.

Research is also moving toward genetic screening. Within the next five years, doctors may be able to identify high-risk people before symptoms even appear-using polygenic risk scores. Imagine knowing you’re at risk at age 25, and getting annual hearing tests to catch it early.

Why So Many People Are Misdiagnosed

One of the biggest problems? Delayed diagnosis. A 2023 study from Tampa General Hospital found 22% of patients waited an average of 18 months before getting the right diagnosis. Why? Because doctors often mistake it for Eustachian tube dysfunction, allergies, or just “getting older.” Primary care providers aren’t trained to spot the subtle signs of conductive loss. If you’ve had unexplained hearing loss for over six months, especially with tinnitus and low-pitch trouble, ask for an audiogram. Don’t wait.

What Life Is Like After Diagnosis

Patients who get treated often say their quality of life improves dramatically. One teacher in her 40s said she could finally hear her students whispering in the back row after surgery. Another said she stopped missing her grandchildren’s first words. On patient forums, 92% of those who had stapedotomy reported significant improvement in daily functioning.

But it’s not all smooth. Tinnitus is a big issue-80% of patients report it, and 35% say it ruins their sleep. Some feel isolated, especially if they’ve been misdiagnosed for years. Support groups like the Hearing Loss Association of America have over 1,200 members with otosclerosis. Talking to others who’ve been there helps more than you’d think.

What’s Next for Otosclerosis?

The number of surgeons performing stapedectomies is dropping. Younger otolaryngologists are focusing on cochlear implants and advanced hearing tech. That means access to expert care is becoming harder in some areas. But the condition itself isn’t going away. With better screening and new prosthetics, otosclerosis will remain the third most common cause of adult hearing loss through 2040.

The future isn’t just about fixing the bone. It’s about stopping it before it starts. Genetic testing, targeted drugs, and early intervention could turn otosclerosis from a life-altering condition into a manageable one.

If you’ve been struggling to hear low voices, if whispers feel impossible, if your hearing’s been slowly slipping for years-it’s not just age. It might be otosclerosis. And it’s fixable.

Can otosclerosis cause complete deafness?

No, otosclerosis rarely leads to total deafness. Even without treatment, most people retain some level of hearing. With hearing aids or surgery, 90% of patients regain functional hearing. The condition mainly causes conductive hearing loss, which is highly treatable. In rare cases where it spreads to the inner ear, sensorineural loss can occur, but even then, hearing aids or cochlear implants can help significantly.

Is otosclerosis hereditary?

Yes, genetics play a strong role. About 60% of people with otosclerosis have a family member with the condition. Researchers have identified 15 genetic loci linked to it, with the RELN gene on chromosome 7 being the most significant. If a parent has otosclerosis, your risk is higher-but having the gene doesn’t guarantee you’ll develop symptoms. Environmental factors like viral infections and hormonal changes also influence whether the condition becomes active.

How is otosclerosis diagnosed?

Diagnosis starts with a pure-tone audiogram, which shows a conductive hearing loss pattern with an air-bone gap of at least 15 dB. Speech discrimination is usually normal in early stages. A tympanogram may show normal eardrum movement, ruling out fluid or blockages. If otosclerosis is suspected, a high-resolution CT scan of the temporal bone can reveal early bone changes around the stapes. A specialist will also check for tinnitus and rule out other conditions like Meniere’s disease or Eustachian tube dysfunction.

Can hearing aids cure otosclerosis?

No, hearing aids don’t cure otosclerosis-they only manage the symptoms. They amplify sound to compensate for the blocked transmission in the middle ear. They’re a great option for mild cases or if you’re not ready for surgery. But they don’t stop the bone growth. Over time, as the condition progresses, hearing aids may become less effective, especially if inner ear damage develops. Surgery is the only way to restore the natural mechanics of hearing.

What’s the difference between stapedotomy and stapedectomy?

Stapedectomy removes the entire stapes bone and replaces it with a prosthesis. Stapedotomy, the modern standard, removes only part of the stapes footplate and inserts a tiny piston into a drilled hole. Stapedotomy is safer, has fewer complications, and better preserves inner ear function. It’s now the preferred method in most clinics. Success rates are higher (90-95%) and recovery is quicker. Stapedectomy is rarely done today except in complex revision cases.

How long does recovery take after stapedotomy?

Most people return to light activities within a few days. Full recovery takes about 2-4 weeks. You’ll need to avoid heavy lifting, flying, and swimming for at least a month to prevent pressure changes. Hearing improves gradually-some notice better hearing within days, but it can take up to six weeks for the full effect as the ear heals. Dizziness and tinnitus are common in the first week but usually fade. Your surgeon will schedule a follow-up audiogram at 6-8 weeks to measure improvement.

Is otosclerosis more common in women?

Yes, women are diagnosed with otosclerosis about twice as often as men. It’s most common between ages 35 and 45, and symptoms often worsen during pregnancy, suggesting estrogen may trigger or speed up bone remodeling. Hormonal changes may explain why women are more affected. However, men can and do develop it too-just less frequently and often at a slightly older age.

Can otosclerosis be prevented?

There’s no proven way to prevent otosclerosis, since it’s largely genetic. But early detection can prevent major hearing loss. If you have a family history, get baseline hearing tests in your 20s or 30s. Avoid excessive noise exposure, which may stress the inner ear. Some doctors recommend sodium fluoride supplements for high-risk patients to slow progression, though this is still being studied. The best prevention is awareness-know the signs and seek help early.

Comments (9)