Why Illegible Handwriting on Prescriptions Still Kills People

Every year in the U.S. alone, over 7,000 people die because a doctor’s handwriting was too messy to read. That’s not a guess. It’s from the Institute of Medicine. These aren’t rare cases. They’re preventable mistakes that happen because a prescription scribbled on paper got misread by a pharmacist, nurse, or even a busy doctor trying to rush between patients.

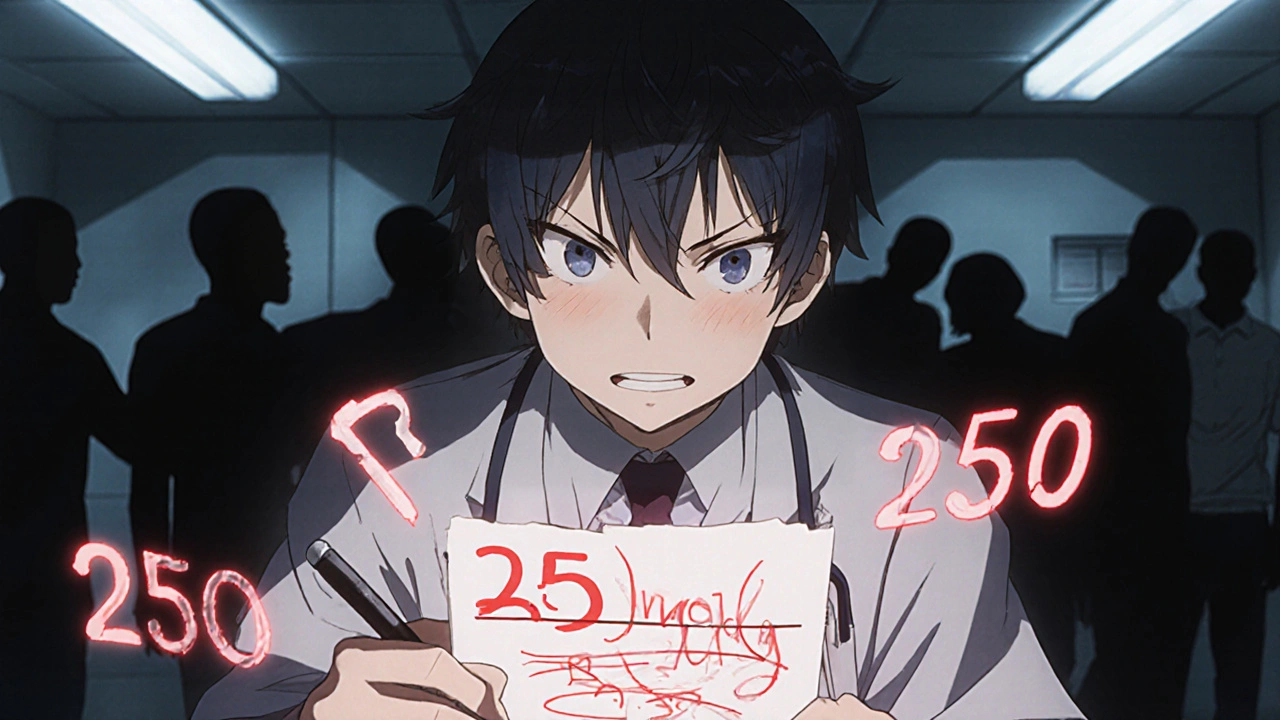

Imagine this: A patient gets a prescription for metoprolol-a heart medication. The doctor meant to write 25 mg once daily. But the handwriting looks like metoprolol 250 mg. The pharmacist fills it. The patient takes it. Within hours, their blood pressure drops dangerously low. They end up in the ER. This isn’t fiction. It’s happened. And it still happens, even in 2025.

Handwritten prescriptions are outdated. They’re slow. They’re risky. And despite decades of warnings, many clinics and hospitals still use them-especially in underfunded areas or among older doctors who never fully switched to digital tools.

The Real Cost of Bad Handwriting

It’s not just about deaths. Illegible prescriptions cause delays, extra tests, unnecessary hospital visits, and massive waste of time. In the U.S., pharmacists make over 150 million phone calls each year just to clarify what a doctor wrote. That’s 150 million interruptions. 150 million moments where a pharmacist has to pause their work, track down a provider, and hope they’re not on another call.

Nurses aren’t spared either. A 2019 study found that for every illegible prescription, nurses spend an average of 12.7 minutes trying to figure out what was meant. Multiply that by 10 prescriptions a shift. That’s over two hours lost just to decoding bad handwriting-time that should be spent with patients.

And the errors aren’t always obvious. Doctors might use abbreviations like “QD” for daily (which can be mistaken for “QID” - four times a day), or write “U” for units (which looks like a zero or a 4). The Joint Commission banned these abbreviations over 20 years ago. Yet, they’re still out there.

How Common Are These Mistakes?

More than you think. A 2022 study found that 92% of medical students and doctors made at least one prescription error due to handwriting. On average, each person made two errors. That’s not incompetence. It’s pressure. Doctors are rushed. They’re juggling 30 patients a day. Writing clearly takes time they don’t have.

In a 2005 audit of surgical notes in a British hospital, only 24% were rated as “excellent” or “good” for legibility. Nearly 4 in 10 were labeled “poor.” That’s not a one-off. That’s a pattern.

And here’s the scary part: 22% of healthcare workers admitted they’d just ignore illegible prescriptions and guess what was meant. That’s not negligence-it’s survival. When you’re swamped, you take shortcuts. But shortcuts cost lives.

The Solution Is Already Here: E-Prescribing

The fix isn’t complicated. It’s electronic prescribing-e-prescribing. No handwriting. No guessing. No abbreviations. Just clear, typed orders that go straight from the doctor’s screen to the pharmacy’s system.

Studies show e-prescribing cuts errors from illegibility by 97%. That’s not a small win. That’s life-changing. In a 2025 study published in JMIR, e-prescriptions had an 80.8% accuracy rate for safety rules. Handwritten ones? Just 8.5%. That’s a 900% improvement.

Even when clinicians typed e-prescriptions from scratch-without templates-they still hit 56% accuracy. That’s more than six times better than pen on paper.

By 2019, 80% of U.S. office-based doctors were using e-prescribing. The trend is unstoppable. Medicare and Medicaid started offering financial bonuses for using it in 2008. The 21st Century Cures Act in 2016 made interoperability mandatory. Systems now talk to each other. Prescriptions follow patients across pharmacies and clinics.

Why Haven’t We Gone Fully Digital Yet?

Cost. Training. Resistance.

Switching to a full e-prescribing system can cost a small clinic $15,000 to $25,000. Add staff training-8 to 12 hours per provider-and integration with existing electronic health records, and it’s a big lift for under-resourced practices.

Some doctors hate the extra clicks. Others worry about alert fatigue-when the system pings them with too many warnings, they start ignoring them. One study found that clinicians sometimes override safety alerts just to move on. That’s a new kind of risk.

And in rural areas or developing countries, internet access or reliable power can be a problem. That’s why handwritten prescriptions still exist. But they’re becoming the exception, not the rule.

What If You Can’t Switch to E-Prescribing Right Now?

If you’re still writing prescriptions by hand, here’s how to cut the risk-today:

- Print, don’t cursive. Block letters are easier to read than loops and swirls.

- Avoid banned abbreviations. No “U” for units. No “QD” or “QID.” Write out “daily” or “four times a day.”

- Always include the route. Is it oral? IV? Topical? Don’t assume.

- Use exact numbers. Write “5 mg,” not “5 mg PO.” Don’t write “1 tab” - write “1 tablet of 25 mg.”

- Sign and date everything. No initials. Full name. No exceptions.

- Double-check high-risk drugs. Insulin, warfarin, opioids-these need extra care. Write them in full: “insulin glargine 10 units,” not “insulin 10.”

Some clinics have started using a 15-item checklist for handwritten prescriptions. Doctors self-assess before sending them out. It’s not perfect-but it cuts errors by 30% in just a few months.

The Future: AI and Handwriting Recognition

What about places that can’t afford full e-prescribing systems yet? There’s emerging tech that might help.

Artificial intelligence is now being trained to read handwritten prescriptions. Early tools can recognize common drug names with 85-92% accuracy. Imagine a nurse scanning a scribbled note on a tablet. The app pops up: “Did you mean metformin 500 mg twice daily?”

This isn’t science fiction. It’s being tested in clinics in India, Nigeria, and rural U.S. counties. It’s not a replacement for e-prescribing-but it’s a bridge. A safety net while systems catch up.

What’s Next?

By 2030, handwritten prescriptions will be nearly extinct in developed countries. The data, the regulations, and the economics all point in one direction: digital is safer, faster, and cheaper in the long run.

But change doesn’t happen overnight. It takes policy, investment, training, and culture shift. The biggest barrier isn’t technology. It’s habit.

Doctors who’ve written prescriptions by hand for 30 years don’t want to learn new software. Pharmacists who’ve spent years deciphering scribbles are used to the chaos. But every time someone ignores a messy script, someone risks their life.

The question isn’t whether we should go digital. It’s why we waited so long.

What Patients Can Do

You don’t have to wait for the system to fix itself. Here’s how to protect yourself:

- Ask your doctor to print the prescription clearly-or send it electronically to your pharmacy.

- When you pick up your meds, read the label. Does it match what your doctor told you?

- If the dose seems too high or too low, ask the pharmacist to double-check.

- Don’t be afraid to say: “I don’t understand this. Can you explain it again?”

Your life is worth the extra five minutes.

Comments (9)