When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it’s truly the same? The answer lies in pharmacokinetic studies-the most widely used method to prove that a generic drug behaves the same way in your body as the original. Yet calling it the "gold standard" is misleading. It’s not perfect. It’s not always enough. And for some drugs, it’s barely even the best option.

How Pharmacokinetic Studies Work

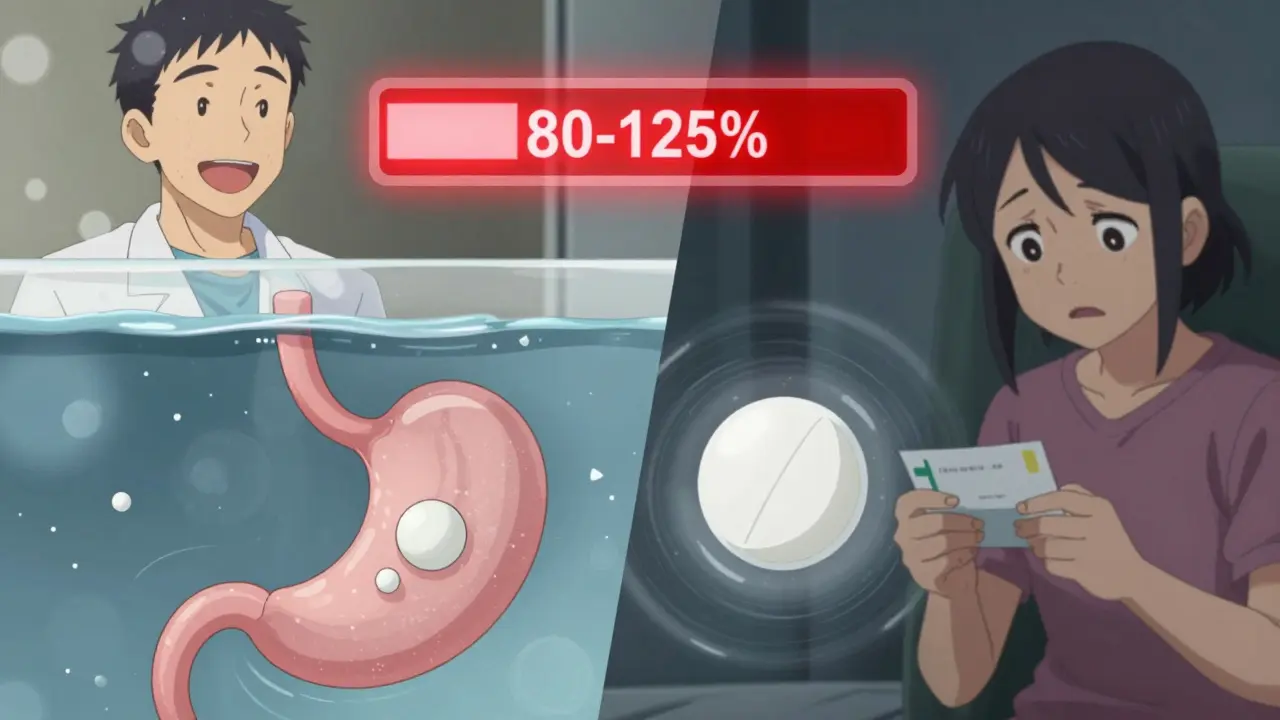

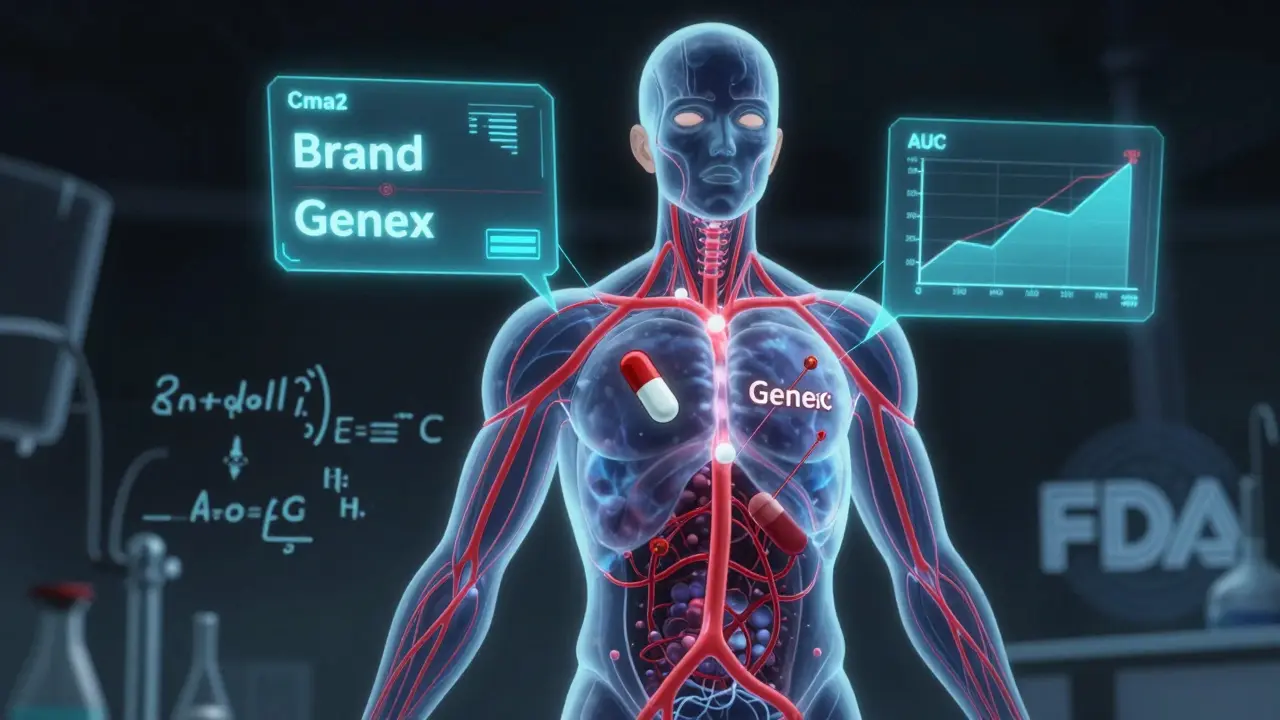

Pharmacokinetic studies track how your body handles a drug after it’s taken. The main focus? Two numbers: Cmax and AUC. Cmax is the highest concentration the drug reaches in your blood. AUC measures the total amount of drug your body absorbs over time. These aren’t just lab curiosities-they tell regulators whether the generic drug gets into your bloodstream at the same rate and to the same extent as the brand-name version. These studies are done in healthy volunteers, usually between 24 and 36 people. Each person takes both the generic and the brand-name drug, often in a random order, with a clean break in between. The tests are run under two conditions: fasting and after eating. Why? Because some drugs absorb poorly on an empty stomach. If a drug’s absorption changes with food, regulators need to know that the generic behaves the same way in both situations. The results are analyzed statistically. The 90% confidence interval for the ratio of generic to brand-name drug must fall between 80% and 125% for both Cmax and AUC. That’s the FDA’s rule. If the numbers land outside that range, the generic doesn’t get approved. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, phenytoin, or digoxin-the bar is higher. The acceptable range tightens to 90-111%. One percentage point outside, and the drug gets rejected.Why Pharmacokinetic Studies Are the Default

The system we use today was set up in 1984 by the Hatch-Waxman Act. Before that, generic manufacturers had to run full clinical trials to prove their drugs worked. That cost millions and took years. Hatch-Waxman changed that. It said: if the generic has the same active ingredient, dose, and form as the brand, and if it behaves the same in the body (as shown by pharmacokinetic studies), then you don’t need to re-prove it works for every condition. It was a game-changer. Today, 95% of generic drugs approved by the FDA get through this pathway. The global generic drug market is worth nearly half a trillion dollars. Without pharmacokinetic studies, most of those drugs wouldn’t exist-or they’d cost 10 times more. But here’s the catch: this system assumes that if the drug enters your blood the same way, it will work the same way. That’s usually true. But not always.The Limits of Pharmacokinetic Studies

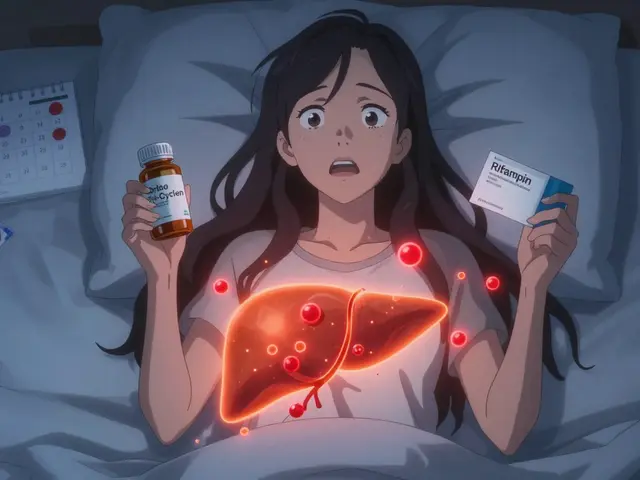

Take gentamicin, an antibiotic. In one study, two generic versions of gentamicin showed identical absorption profiles to the brand-name drug. Their Cmax and AUC were within the 80-125% range. Yet when tested in patients, one generic failed to kill the same bacteria as the original. The in vitro tests looked perfect. The pharmacokinetic data looked perfect. But the clinical outcome wasn’t. Why? Because the drug’s effectiveness depended on how it interacted with bacterial cell walls-not just how much entered the bloodstream. That’s the flaw in relying too heavily on pharmacokinetics. It measures what the body does to the drug. It doesn’t measure what the drug does to the body. This problem is worse with complex formulations. Think of extended-release pills, inhalers, creams, or injectables. For topical creams, measuring drug levels in blood tells you almost nothing. The drug isn’t meant to enter the bloodstream-it’s meant to act on the skin. A study in Frontiers in Pharmacology found that for these drugs, testing on human skin in a lab (in vitro permeation testing) was more reliable and less variable than trying to measure blood levels in people. Even for oral drugs, things get tricky. Minor changes in fillers, coatings, or manufacturing processes can alter how fast a pill breaks down-even if the active ingredient is identical. One manufacturer’s generic might dissolve in 15 minutes. Another’s might take 25. Both could pass the Cmax and AUC test. But in a patient with slow digestion, one might release too slowly. That’s not a failure of the test-it’s a failure of the assumption that absorption equals effect.

What Happens When Pharmacokinetics Isn’t Enough?

For drugs where blood levels don’t predict outcomes, regulators turn to other tools. For asthma inhalers, they use lung deposition studies. For eye drops, they measure drug concentration in the tear film. For anticoagulants like warfarin, they monitor blood clotting times directly. These are clinical endpoint studies-and they’re expensive. One study might need 500+ patients. That’s why they’re rarely used for routine approval. But for high-risk drugs, they’re necessary. The FDA now has specific guidance for 28 narrow therapeutic index drugs. For these, pharmacokinetic studies alone aren’t enough. You need extra data-sometimes even post-market monitoring. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) takes a stricter approach than the FDA. It applies the same 80-125% rule to almost everything. The FDA, on the other hand, has over 1,800 product-specific guidances. That means a generic version of one drug might need a blood test. Another might need a dissolution test. Another might need a clinical trial. It’s messy-but it’s more precise.The Rise of New Tools

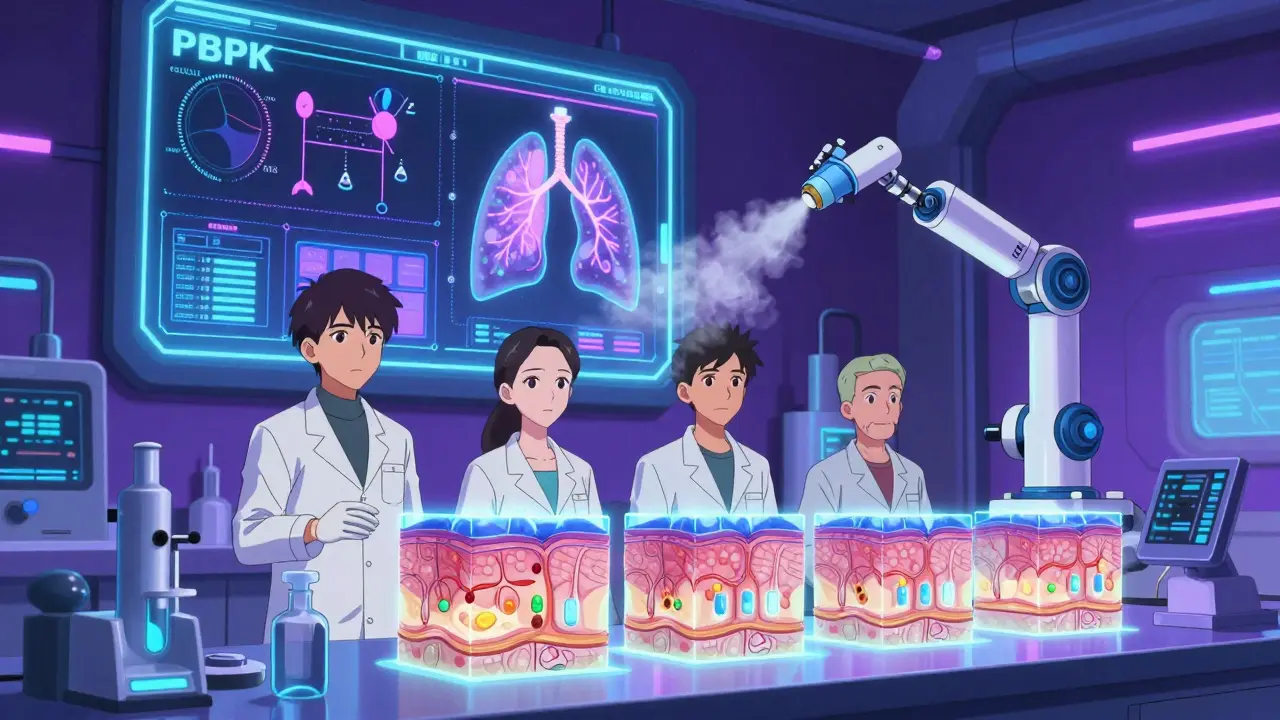

The field is changing. One promising alternative is physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling. Instead of testing on people, scientists use computer models that simulate how the drug moves through the body based on anatomy, enzyme activity, and gut pH. The FDA has accepted PBPK models to waive bioequivalence studies for certain BCS Class I drugs-those that dissolve easily and absorb quickly. In vitro testing is also gaining ground. For some immediate-release tablets, lab tests that mimic stomach conditions can predict real-world performance better than human trials. One 2009 study even argued that in vitro methods were sometimes more reliable than human pharmacokinetic studies. And for topical drugs, dermatopharmacokinetic methods are showing promise. By measuring drug levels directly in the skin layers, researchers can predict effectiveness without drawing blood. One study showed these methods could detect differences between formulations with over 90% accuracy.

Cost and Complexity

Running a single pharmacokinetic study costs between $300,000 and $1 million. It takes 12 to 18 months from formulation to approval. For small manufacturers, that’s a huge barrier. That’s why many companies work with contract research organizations and use the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) to try to get waivers. Only about 15% of drugs qualify for a BCS-based waiver, but for those that do, it saves millions. The process isn’t just expensive-it’s unpredictable. Two companies making the same generic drug might get different results because of tiny differences in manufacturing. One might pass. The other might fail. That’s not a flaw in the science. It’s a flaw in the system: we’re trying to measure a complex biological process with a single set of numbers.What This Means for You

You can trust that most generic drugs work just like the brand. The system works well for the vast majority of medications. But it’s not foolproof. If you’re taking a drug with a narrow therapeutic index-like thyroid medicine, seizure drugs, or blood thinners-and you notice a change in how you feel after switching generics, talk to your doctor. It’s rare, but it happens. The goal isn’t to scare you away from generics. It’s to understand that "same active ingredient" doesn’t always mean "same effect." Pharmacokinetic studies are the best tool we have for most drugs. But they’re not the whole story.What’s Next for Generic Drug Approval?

The future is personalized. Regulators are moving away from one-size-fits-all rules. More product-specific guidelines are being developed. More advanced models are being validated. More non-blood-based tests are being accepted. For now, pharmacokinetic studies remain the backbone of generic approval. But they’re becoming one part of a bigger toolkit. The real gold standard isn’t a single test. It’s a combination of science, data, and real-world evidence-all working together to make sure every pill you take does what it’s supposed to.Are pharmacokinetic studies always required for generic drugs?

No. For some drugs-especially those that dissolve easily and are absorbed quickly in the gut (BCS Class I)-regulators may accept in vitro testing or computer modeling instead. The FDA allows waivers for about 15% of drug products based on the Biopharmaceutics Classification System. But for most oral medications, pharmacokinetic studies are still required.

Can two generics with the same active ingredient work differently?

Yes. Even if two generics have identical active ingredients, differences in fillers, coatings, or manufacturing can affect how quickly the drug is released or absorbed. In rare cases, this leads to differences in effectiveness or side effects-especially with narrow therapeutic index drugs like warfarin or levothyroxine. That’s why some patients notice changes when switching between brands of generics.

Why do some countries reject generics that pass FDA tests?

Different regulatory agencies have different standards. The EMA, for example, applies the same 80-125% bioequivalence range to all drugs, while the FDA uses product-specific guidelines. Some countries also require additional clinical data or stricter dissolution testing. A generic approved in the U.S. might not meet the criteria in the EU or Japan.

Do pharmacokinetic studies test for side effects?

Not directly. Pharmacokinetic studies measure drug levels in the blood, not how the body reacts to them. Side effects are usually monitored in the same study, but only as safety observations-not as primary endpoints. If a generic causes more side effects, it might still pass bioequivalence if its absorption profile matches the brand. That’s why post-market surveillance is critical.

Is there a better way to prove generic equivalence than pharmacokinetic studies?

For some drugs, yes. For topical creams, in vitro skin permeation tests are more accurate. For inhalers, lung deposition studies are preferred. For drugs with narrow therapeutic windows, clinical endpoint studies-measuring actual patient outcomes-are the most reliable. The trend is moving toward using the best method for each drug, not forcing everything into one mold.

Comments (12)